SURF: Cool Research for a Hot Summer

Summer Undergraduate Research with Faculty (SURF) grants kept CofC students busy this season. Here's just a few of their projects.

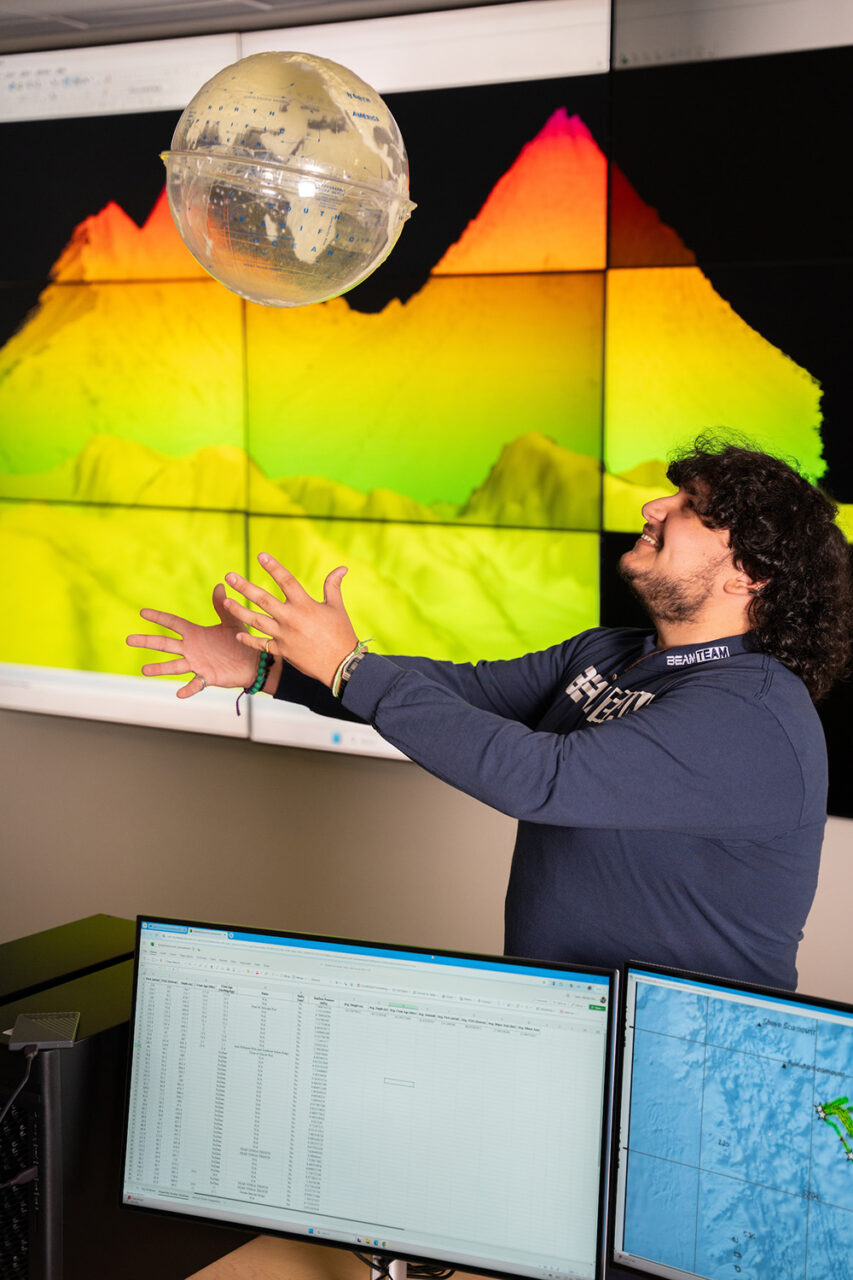

Above: Biology major Nikolai Sarlo, who spent the summer developing a submarine volcano database in order to focus monitoring efforts on the most dangerous volcanoes (photo by Catie Cleveland)

Each summer, students at the College of Charleston gain hands-on experience through Summer Undergraduate Research with Faculty (SURF) grants, which pair students with faculty mentors to pursue experiential research that tackles real-world issues.

“Faculty-student collaboration in a challenging, scholarly project can be the single most transformative experience that a student will have in college,” says Beth Sundstrom, director of the Undergraduate Research and Creative Activities (URCA) Program and professor of communication. “In addition to technical skills, students develop professional skills, including problem-solving, communication, teamwork, leadership and creativity. These transferable skills apply to any future educational or career goals.”

Below are six of the 23 student projects that received SURF grants for summer 2025.

Reaching New Heights for Drones

Last year, mysterious drone sightings alarmed residents of New Jersey and other East Coast states, even shutting down an airport at one point.

Turns out, they were authorized by the FAA for research and other purposes, combined with drones flown from curious hobbyists. The problem is, all drones look alike, especially at night. But they don’t sound alike, according to computer science major Andrew Berg, who is using AI to study the audio signature of drones to develop a classification system.

Under the guidance of assistant professor of computer science Mia Wang, Berg’s project involves training advanced computer models to recognize patterns in drone sounds, similar to how humans identify voices or musical notes, or even how the Shazam app can identify songs.

Technology and Applications in Bilbao, Spain, on June 12.

“All audio has the potential to have different audio signature,” Berg says. “Even if we can’t perceive it, there are slight differences. This is why it is so exciting to get to work with AI systems that go beyond human cognition.”

Intelligent defense systems need to be able to have more information about a given UAV to protect people, but it is prohibitively expensive to own/rent UAVs and record their audio. Berg is addressing this issue of scale by asking, “How can our AI do more with less?”

“As the growth of UAVs skyrockets, we need answers,” he says.

Berg’s SURF grant allowed him to travel to Bilbao, Spain, in June to present his research paper, “4,500 Seconds: Small Data Training,” at the 14th International Conference on Data Science, Technology and Applications.

“Working in Dr. Wang’s Drone lab has given me the opportunity to meet and work with some amazing individuals, who inspire me to stay curious,” he says. “It’s been life-changing.”

– Tom Cunneff

Defining a Language

Revising a dictionary isn’t the most common summer activity. But for senior Isaac Hill, it was an opportunity to work with a group of Nicaragua’s Indigenous people and help preserve Yusku, a variant of the Mayangna language.

“I think a big reason it’s important to study indigenous languages is that they offer us data that we can’t find in other places,” says Hill, a cello player and composer majoring in music and minoring in linguistics. “If they do go extinct, if we don’t document them and – even beyond documenting – if we don’t teach younger generations of speakers, there are literal scientific discoveries that can’t be made because the data is just gone.”

Hill learned about the effort to create a Yusku dictionary while taking Indigenous Languages of the Americas with Ricard Viñas-de-Puig, associate professor of Spanish and director of linguistic studies, who is part of the project. Hill worked with the research team in the summer and winter of 2024 before securing a SURF grant to continue his work this summer.

The project is a collaboration between native Yusku speakers and local and external linguists using the participatory action research (PAR) methodology. Developed for linguistic research, this methodology upholds Indigenous peoples’ goals for the project and prioritizes a mutual exchange of knowledge between Indigenous and external participants.

“I think the PAR methodology and general respect for the agency of Indigenous communities applies to any research and talking or working with Indigenous people,” Hill says.

Native Yusku speakers recognized a need to preserve the language and help formalize how it’s taught to young students. The collaborative effort led to the first-ever Yusku dictionary published in early 2025.

Hill now works with other students, researchers and native speakers to expand and revise the existing dictionary into a second edition.

“As a linguist, I think a lot of the morphology of the language is really cool, and it’s very different from any Indo-European language. It just kind of turns all the things we would assume from more commonly spoken languages on their head,” he says. “It’s very cool to learn about the capabilities of human language. That ultimately informs us about the mind and what humans are capable of.”

Hill draws connections between his current research and his studies in music, too.

“I think there are a lot of intersections between language and music,” says Hill, adding that he hopes to continue working on the Yusku project through a musicological lens, focusing on indigenous musical traditions using the PAR approach.

– Samantha Connors

Connecting People, Art and Technology

For Hayes Martini, art is about human connection. But – as artistic tools, mediums and methods become more technologically advanced – creating art can lose some of that human touch. But, Martini thought, doesn’t have to.

To bridge technology and art, Martini developed her summer research project, Human Contributions to Digital Fabrication, transforming digital photographic images into three-dimensional sculptures using 3D printing, laser cutting and CNC plasma cutting and experimenting with materials like PLA plastic, plywood, plexiglass, steel and aluminum.

The senior studio art major designed her project “to explore how technology can enhance the human experience often consumed by the digital world.”

“Art is about connection, so I did want to bring that human element into it,” says Martini, who is fascinated by environmental portraiture because of how personal and intimate it can be to capture someone in their own space. “It often leads to deeper and more valuable conversations when they are in a comfortable and familiar space.”

And so that’s where she started – by visiting people in their own spaces. Specifically, she connected with women over the age of 65 who have lived in Charleston their entire lives. Using the Nextdoor app, she found six women who allowed her to visit them in their homes, where she interviewed and photographed them.

“I was surprised how open the women were,” she says. “They kindly welcomed me into their homes and shared their stories and spaces with me.”

It turns out, that was the easy part. It was the challenge of connecting the women’s homes to technology that excited her.

Martini, whose focus had always been photography, was introduced to the cutting-edge technology and expanded possibilities in the new Simons Center Sculpture Studio while taking sculpture classes with Jarod Charzewski, assistant professor of studio art. Intrigued by the art form, she wanted to take the familiarity of photography and manifest it through sculpture.

“Once I had the photography portion, I thought, I’m going to create a fictitious living room,” says Martini, who – after compiling her photography into a book, The Women Who Stayed – used the highly technological equipment in the Sculpture Studio to make replicas of items she photographed in the women’s homes. The installation she created combines the homes and interviews of all the women through things like tables, knickknacks, clocks, wood paneling and shelving. From the fabric of the chair inspired by the wallpaper in one of the women’s houses to the framed cross-stitched quotes (“Calculated Risk” and “Never Sold My Soul for a Job”) taken from the women’s interviews: Everything she created connected to the women. “I was able to work with older women and technology and connect the two in an unexpected way.”

“Because we now have the new access and support of technology in the new studio, we can think of these things and actually do them,” says Charzewski. “With all this technology available and accessible, so much more is at our fingertips. And it’s becoming more and more second nature to use this equipment and technology – something that’s much more intuitive to younger generations.”

“I had never done any of this before. I was ready for something new,” says Martini. “I was a novice sculptor, but now I have the confidence to work with all sorts of equipment and technology, and I know I can build pretty much anything!”

– Alicia Lutz

Advancing Neonatal Stroke Recovery

Sometimes one class can change everything. For Aniston Hong, a senior and majoring in biology with a minor in neuroscience, it was Anatomy.

That class is where she first saw the brain not just as an organ, but as a key to understanding the body – sparking a curiosity that led her to neuroscience research focused on neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), a type of stroke that affects newborns.

Hong’s interest in stroke research is personal.

“My grandfather had a stroke when I was younger,” she says. “I didn’t understand it at the time, but once I started learning about neurology, I thought back to him. I wanted to understand how something in the brain could affect the whole body.”

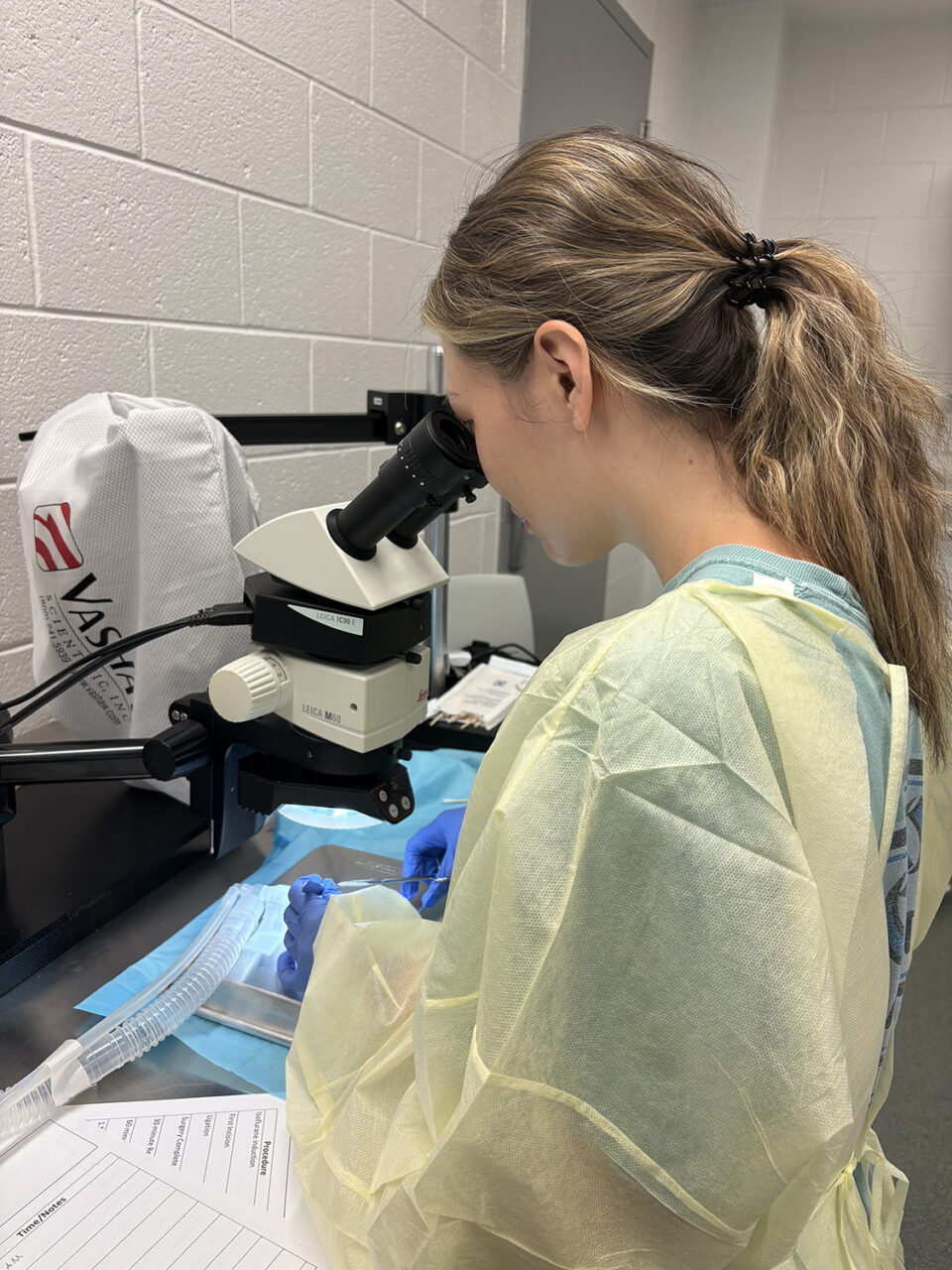

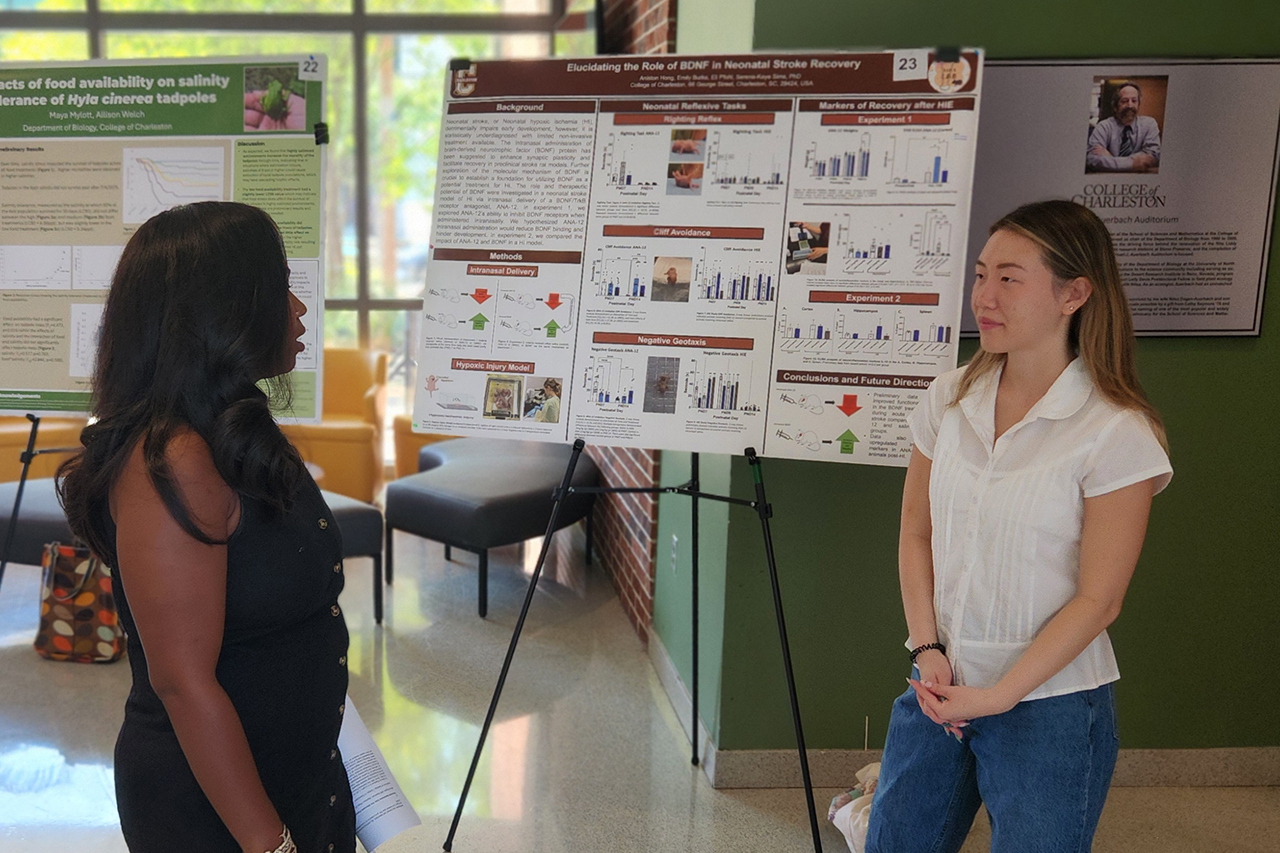

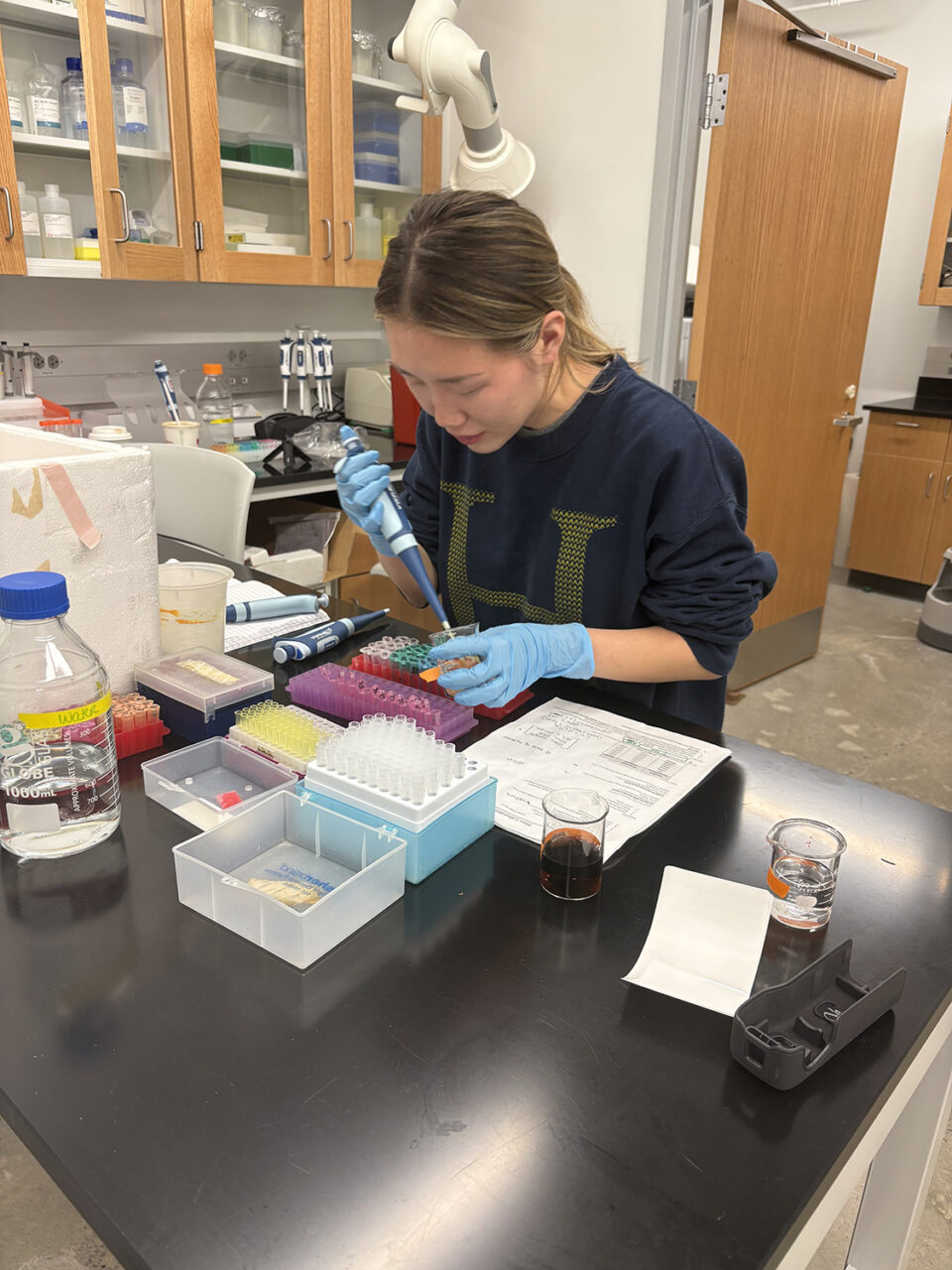

Ever since her sophomore year, Hong has been working in the lab of Serena Kaye Sims, an assistant professor in biology known for her work in developmental biology and neurogenetics. The SURF grant gave her the chance to help wrap up a long-running study and spend the summer immersed in full-time research – including caring for lab rats, conducting behavioral tests, performing surgeries and dissections and analyzing tissue samples.

“I wanted to build on what we’d started and learn more about how strokes affect the developing brain,” says Hong, who also worked on a research poster and a publication based on the lab’s preliminary data. “The most rewarding part has been seeing the data come together. It’s exciting to think that what we’re learning could help improve treatment for neonatal stroke patients.”

After graduation, Hong plans to pursue a career in OB-GYN, specializing in fetal surgery. Her advice to other students? “Find a lab that genuinely interests you. When you care about the work, the experience becomes so much more meaningful.”

– Amy Stockwell

Easing the Impact of Submarine Volcanoes

Nikolai Sarlo is the first to admit that he pretty much hunted down Haley Cabaniss ’15, assistant professor of geology and environmental geosciences and director of College’s Benthic Acoustic Mapping (BEAMS) Program, to talk to her about seafloor mapping.

“I’m so glad I did,” says the biology major with a double minor in geoinformatics and marine geology, explaining that Cabaniss is passionate about seafloor mapping. “I found myself falling more in love with the concept. Seafloor mapping has both a creative and exploratory side that really spoke to me.”

Fortunately, the two hit it off quickly, and this summer they paired up on a SURF project to expand a submarine volcano database and determine traits that help identify which ones pose a threat and which do not.

“You can tell which volcano is dangerous based on its shape and depth,” says Sarlo, whose summer work involved significant mapping and comparison with an existing satellite survey. “It takes us hours and is a very tedious process to go through each one.”

For Sarlo, the discoveries are worth the effort. Submarine volcanoes can be incredibly hazardous and capable of generating tsunamis, damaging underwater infrastructure and disrupting shipping routes. Determining the eruption and hazards of submarine volcanoes helps focus monitoring efforts on the most dangerous volcanoes, increasing our ability to predict and mitigate the impacts of their eruption.

Sarlo had honed his skills through BEAMS, a unique program that offers undergraduate-focused training and research with the mission of developing a strong and qualified workforce of ocean surveyors in support of the academic, research and operational marine communities.

“Students in this program learn about the geology of the seabed, the fundamentals of sonar theory and data processing, and pursue an independent research project,” says Cabaniss. “Nikolai was well-prepared for this research project because of his training in the BEAMS Program.”

Sarlo doesn’t just have the training for the project – he has the enthusiasm.

“Nikolai has a passion for maps that is contagious,” says Cabaniss. “This, paired with his curiosity about submarine environments and his desire to engage in science that benefits society, makes him the perfect student to take on this work.”

– Abby Albright

Protecting Smart Grids With AI

Jason Bluhm is helping to provide solutions for smart grid protection against cyberattacks.

Through his research, he aims to develop advanced artificial intelligence–powered solutions to detect anomalies, prevent data breaches and ensure the resilience of smart grids, which are advanced, digitalized electricity networks that use two-way communication and control capabilities to optimize energy delivery, improve reliability and enhance efficiency.

“My interest in smart grid cybersecurity stems from a background that combines military service and computer science” says Bluhm. “I’ve seen firsthand how vital secure infrastructure is.”

He spent the summer working with faculty mentor Mohamed Baza, assistant professor of computer science, to investigate how artificial intelligence tools can enhance cybersecurity in smart grid infrastructure. He also collaborated with other computer science majors, including Alma Lutas and Adwoa Addai, on challenges like dataset preparation, model evaluation and problem-solving.

“Our findings have applications beyond smart grids – including in finance, health care and manufacturing,” says Bluhm. “Being able to explain that clearly to stakeholders will be essential as we take the next steps, like integrating our framework into a federated learning environment.”

As Bluhm prepares for the next steps, he emphasizes the importance of collaboration, transparency and responsible AI development.

“Working on this project deepened my understanding of the responsibility that comes with building AI systems – especially those designed to protect critical infrastructure,” he says. “Trust isn’t just about whether a model gets high accuracy: It’s about whether it behaves reliably in uncertain, real-world conditions, and whether it does so in a way that respects privacy and ethical boundaries.”

– George Johnson