A Paleontologist's Take on 'Jurassic World: Rebirth'

Paleontologist Scott Persons reviews the new 'Jurassic' film and holds it up to the scientific light.

When Jurassic Park premiered in 1993, it was a roaring success – and not just at the box office. The film struck a near-perfect balance of blockbuster storytelling and scientific accuracy, thrilling everyone from the wide-eyed children to the discerning paleontologists in its audience.

“The original Jurassic Park film really was wonderful as a science ambassador, as a mass-media promotion of science literature,” says paleontologist Scott Persons, assistant professor of geology and curator of the Mace Brown Museum of Natural History at the College of Charleston. “It’s through Jurassic Park that most kids learned that birds are dinosaurs. It’s where kids saw the first really good, really scientifically accurate depiction of Tyrannosaurus. It’s how Velociraptor – an entire group of dinosaurs, the raptors – became a household name.”

The dinosaurs in Jurassic Park certainly left an imprint – both accurately depicting the dinosaurs and representing some cutting-edge research in paleontology at the time.

“Since then, there’s been this sort of steady decline in the quality of the paleontology that’s depicted on screen. And unfortunately, Jurassic World: Rebirth continues that trend,” says Persons, who went to see the newest Jurassic movie on opening night and says it’s clear that – as opposed to the first film – no paleontologist had been seriously consulted.

Even one of the film’s central premises – that dinosaurs can only survive in today’s world along a narrow equatorial band, because Earth was much hotter during the Mesozoic Era – is inaccurate. While it’s true that the Earth was warmer, the movie takes this idea too far.

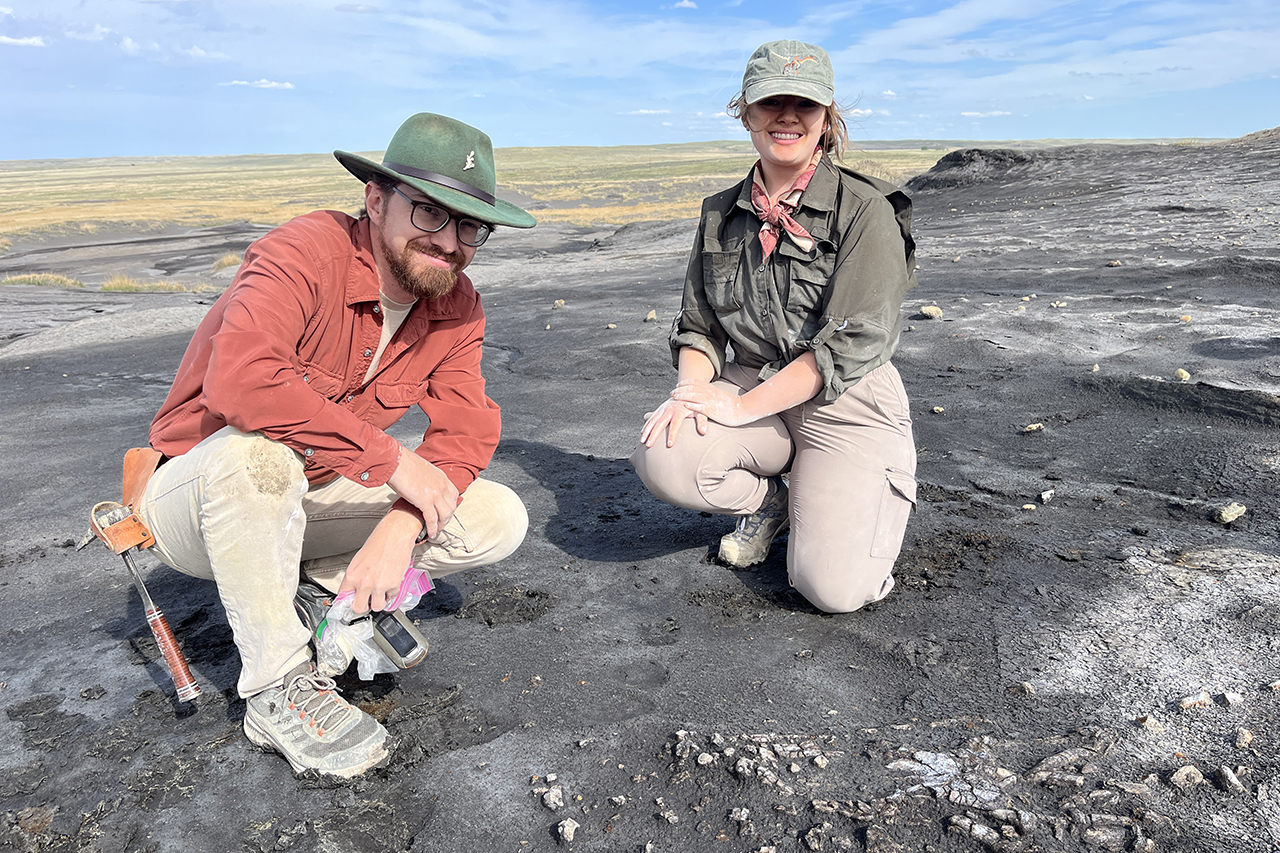

“You find dinosaurs from Antarctica and Australia all the way to Alaska. Even back then, they lived in climates cooler than the tropics,” Persons explains, noting the Tyrannosaurus rex and Triceratops he and his students find when they take CofC Dinosaur Expeditions to Wyoming each summer. “Those environments are actually very comparable to what we have in Charleston right now, so that band of habitable dinosaur range for today certainly extends well into the United States.”

The fossils like the ones Persons and his students find in Wyoming help piece together the world that dinosaurs inhabited – something that the first Jurassic Park film created so well that it could transport audiences back in time to feel what it would be like to see dinosaurs in person.

“The first Jurassic Park was a scientifically refined bit of mental time traveling,” says Persons. “It did something that is the envy of museum exhibitions everywhere: When you go to a science museum, part of what you want to do is to be a time traveler. You want to stand there and imagine what it would be like to be in the presence of dinosaurs, to be back 65 million years ago. Jurassic Park really helped you to have that experience. And that experience is ruined if you know while you’re sitting there that what you’re seeing is inaccurate, that it’s just another fantasy, just another monster movie.”

One of the biggest inaccuracies in Jurassic World: Rebirth is, quite literally, the mosasaurus. The giant marine lizard, which steals the show at the beginning of the movie, is depicted the size of a blue whale – many times larger than any fossil suggests.

“Mosasaurs are big, but not that big,” says Persons.

On the other end of the scale is the titanosaur, said in the movie to weigh 11 tons.

“That is way off,” says Persons, explaining that a big titanosaur could easily weigh over 80 tons. “I don’t know if they thought the audience just wouldn’t believe that an animal could be 80 tons, or what.

“They also sort of mix that animal up: The front end of the animal is a titanosaur, but then they give it a great, big, long, whip-like tail like a Diplodocus,” he adds. “There are long-neck dinosaurs that have tails like that, but they’re not titanosaurs. They got half of it right, though!”

They also got a few other things right – including the little Aquilops.

“It has sort of a weird, almost Saturday-morning-cartoon-sidekick role in the film,” says Persons. “But it really is a cute dinosaur. That dinosaur really is as cute as it looks on film.”

Another successful representation: the Spinosaurus, a crocodile-snouted, meat-eating dinosaur that got its name from its very tall neural spines that are basically extensions of the vertebral column.

“Spinosaurus is a neat animal,” says Persons. “These Spinosaurus are pretty good as far as their anatomy and behavior. They’ve given it a webbed foot, and there are many paleontologists who think that’s accurate. We don’t have preserved skin from Spinosaurus, so we don’t know exactly.”

What we do know from their toe bones is that their claws were very flat, which is consistent with creating a paddle-like shape and at least potentially having a webbed hind foot.

“They might be the best part of film as far as their depictions go, with the one exception of the Tyrannosaurus,” Persons says. “Even though in this version the tail is way too short, overall it’s a pretty good Tyrannosaurus, and the choreography for its scene is also pretty neat.”

The audience, it seems, thought so, too.

“One of the real high points – one that got soft, audible gasps, and you could sort of feel the murmur of excitement in the crowd – was the scene where they stumble across a sleeping Tyrannosaurus,” says Persons, adding that a similar thing happened when they introduced a Velociraptor. “These old, classic dinosaurs, and some of the ones that were done really right, still strike me as being crowd favorites.”

Ironically, in the film, new genetically engineered creatures are created to rekindle the public’s fascination with dinosaurs.

“The theme of this film is that audiences are bored and tired of seeing the same old realistic dinosaurs, so they start creating all these weird mutant hybrid things,” explains Persons. “But the exact opposite was my reading of the crowd: We were all most stoked to see the Tyrannosaurus on the screen. So, at least the audience I saw it with was hungry to see more of the original old dinosaurs, just done well and doing new, interesting things.”

It shows that the people still want “the real thing” out of the Jurassic films.

“There’s a gradient between science fiction and science fantasy,” says Persons. “The first Jurassic Park movie was science fiction: It was a fictional story, but it was largely based around sound science – in thinking critically about what it would be like to see dinosaurs in person. And this film is way on the other side of things. It’s very much so science fantasy. There’s no magic in it, but there’s also no real sound paleontology to it.”

That’s why, on purely academic grounds, Persons says he can’t recommend Jurassic World: Rebirth, though he does recognize its entertainment value.

“As a professor, and thereby something of an intellectual steward for the students at the College of Charleston, I can’t recommend that they go and see the latest Jurassic World film,” he says. “But, if you go, just keep in the back of your mind that there are inaccuracies.”

Films like Jurassic Park prove that entertainment and science don’t have to be at odds. When filmmakers treat the subject matter with curiosity and care, the result is not only more credible, but far more awe inspiring.

“We don’t need to invent fantasy creatures,” Persons says. “Real dinosaurs are already amazing enough.”