What is the Real Story of Thanksgiving?

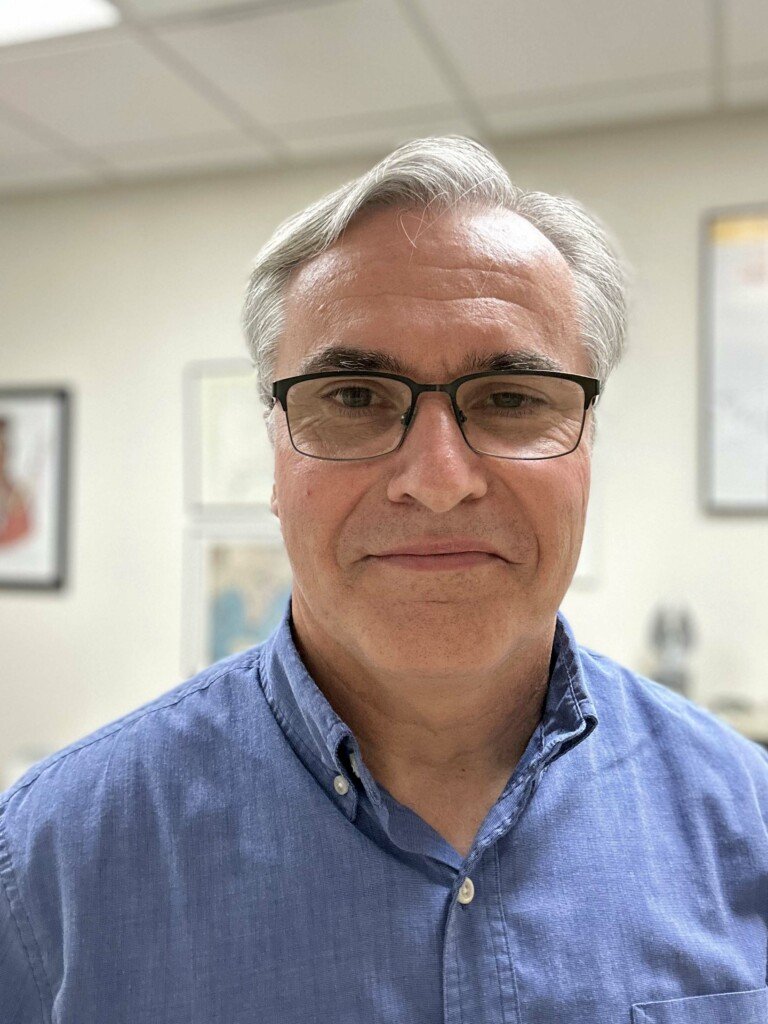

Associate professor of Native American history Christophe Boucher shares some thoughts on the origins of the holiday and why it’s so difficult for Native Americans.

Above: The First Thanksgiving 1621, by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris (Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Just about everyone can get behind the themes of Thanksgiving – gratitude and sharing. But it’s hard for some to be thankful, namely Native Americans, who see the holiday as the beginning of the systematic extermination of their culture by European immigrants. It’s no coincidence that Native American Heritage Day, which began 32 years ago, is the day after Thanksgiving. In fact, all of November is treated as National Native American Heritage Month.

The College Today spoke with Christophe Boucher, an associate professor of Native American history at the College of Charleston since 2001, for a little perspective.

Can you give us an accurate history of Thanksgiving?

Doing so is actually tricky since the documentary evidence available to reconstruct this event is rather scarce. In fact, what we know is based on very succinct statements found in two primary sources: One was written by Edward Winslow and the other by William Bradford, two individuals who lived in the Plymouth colony at the time. From this material, we can conclude that it took place in the fall of 1621. The fact that the authors of these documents did not provide a specific date could indicate that the colonists did not attribute as much significance to this event as we do. The rather succinct description of the event itself would confirm this impression. Bradford’s description, written 20 years after the facts, is too cryptic to get a clear understanding of what actually happened. Winslow’s observations are a bit more informative. According to the latter, at some unspecified date in the fall of 1621, Governor Bradford asked the colonists to come together so that they could, he wrote, in “a special manner rejoice together.” It does not seem that the Wampanoags, who lived close by, had even been invited to the festivities. However, Winslow’s statement suggests that 90 Indigenous men and their leader, Massassoit, were drawn toward the settlement when, at some point during the event, the colonists fired some weapons. Winslow then added that colonists “entertained and feasted” the visitors for three days.

So there really wasn’t this kumbaya moment with the Wampanoags that most people assume, but the tribe was instrumental in helping the first Pilgrims survive. What do you know about them?

The Wampanoags spoke an Algonquian language, and their name means “People of the First Light” after the geographic location of their homeland on the Eastern Seaboard. Their territory stretched from Cape Cod to the eastern edge of Narragansett Bay and from Nantucket Island to Norfolk County (Mass.). The term refers to an alliance of some 30 Algonquian polities located in the region. Among these were the Patuxets, the Mashpees and the Nausets. At the time of contact with the Puritans, Ousamequin, a Pokanoket, had risen to political prominence among the Wampanoags. “Massassoit” was actually his title. It is likely that the Wampanoag Confederacy was founded at an undetermined date as a result of tensions with neighboring Indigenous polities. It is difficult to estimate the size of the population on the eve of colonization, but it could have counted up to 40,000 individuals.

At the time of contact, they had a mixed economy based on agriculture, fishing, hunting and gathering. Each community was led by a leader (Sachem) who received this title from his mother’s clan since the Wampanoags were matrilineal. Based on primary sources of English provenance, Sachems held a number of prerogatives. Among other things, they could allocate land to fellow community members who had to give them tribute in return. The items thus acquired were redistributed strategically to strengthen their authority. Sachems conducted diplomacy with neighboring polities, and they seem to have been responsible for enforcing the law (even though English observers tended to assume that Indigenous leaders had much more power than they did in actuality). They might have also played a critical role in long-distance trade as well, since prized and exotic goods were exchanged between community leaders during diplomatic events. As a so-called Grand Sachem, Ousamequin sat at the top of the political edifice. One of his prerogatives was to conduct inter-tribal diplomacy of behalf of the Wampanoags. In this role, he became a prominent interlocutor between the confederacy and the English, which explains why his name became immortalized in the primary sources.

Why did the Wampanoags allow the English to settle on their land when they could have just as easily pushed them back in the sea when they were at their weakest?

Clearly, Plymouth survived in great part because the Wampanoags helped them. This decision had to do with Indigenous geopolitics. From 1616 to 1618, some epidemic(s) of European origin wreaked havoc among the Wampanoags with dreadful demographic consequences. The Indigenous communities lost as many as 90% of their residents. Interestingly, the Narragansetts, who were the traditional rivals of the Wampanoags, had remained unscathed by the deadly pathogens, which reshaped the regional balance of power. Now the Narragansetts were in a better position to promote their political agenda at the expense of the Wampanoags who had once dominated the region. The erosion of their power was such that the latter, for instance, had to cede some land and pay tributes to the former.

At the same time, the Mi’kmaqs, who lived in what is today Quebec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, intensified their raids on the weakened Wampanoags. The Mi’kmaqs’ access to French trade goods and particularly weapons made of metal, put the Wampaonags at a disadvantage. The sudden materialization of a European colony gave the Wampanoags an opportunity to counterbalance the power of the Narragansetts and other enemies.

How long did they get along for before things turned bad for Native Americans?

When it comes to the souring of relations and signs of things to come, I would point to the treaty that the Wampanoags and the colonists agreed to in March 1621. The document confirmed the alliance between the parties involved against an unspecified third party but, among other things, it also stipulated that any indigenous person guilty of assaulting a colonist would be tried according to English law. Even though an alliance with the English had clear benefits for Massassoit and the Wampanoags, it was also a reminder that the English did not see their Indigenous neighbors as equals. In fact, they expected that Native Americans would submit to their authority. Furthermore, the colonists had little patience with cultural diversity. They also saw the demographic collapse of the local population as evidence that God favored their colonial ambitions and condoned the destruction of those who lived there before.

What ultimately hastened the collapse of diplomatic relations between the English and the Wampanoags was the arrival of thousands of colonists after 1630, which ended up tipping the balance of power in favor of the newcomers. Colonial expansion exacerbated tensions over land use and ownership, as well as a host of other issues. Incidentally, the tendency of colonists to raise semi-feral pigs even contributed to ill feelings, since these voracious animals ruined Native American fields that had traditionally been unfenced. Often the Puritans dismissed indigenous grievances, a cavalier attitude that only exacerbated tensions.

By the mid-1630s, the Puritans saw themselves increasingly as the dominant power in southern New England and did not hesitate to resort to violence to impose their will on the local population. In 1637, for instance, they waged war against the Pequots with such virulence that even the Indigenous peoples who supported the Puritans in this conflict were stunned by the colonists’ inclination to kill women, children and other noncombatants indiscriminately.

Despite the growing grievances, Ousamequin managed to avert war between the Wampanoags and his English neighbors. After his death, his son Metacom (also known to the English as King Philip), threatened by the growing intransigence of the colonists and an erosion of his power, led an attack on the colonists that became known as King Philip’s War. Once the dust settled in 1677, the defeated Wampanoags were no longer in a position to challenge their white neighbors and they quickly became strangers in their own land. A hundred years before the American Revolution, the Wampanoags had fought and lost their own War of Independence.

Given the slaughter and displacement of Native Americans that has taken place in this country, how do they feel about Thanksgiving? Do they even celebrate it?

For the reasons mentioned above, Native Americans do not see Thanksgiving as a cause for celebration. For them, it is a reminder that contact with Europeans has had cataclysmic effects that left them with little political power and hastened their disenfranchisement. And this history has deep ramifications that are still felt today in Indigenous communities across the country.

November is National Native American Heritage Month. What can we do as Americans to celebrate it, and what can we do as a country to right some of the wrongs?

These days, history has become so politicized that trying to set the record straight can trigger disturbing responses. Sadly, some go as far as seeing this endeavor as a treasonous act. As a scholar, I think it is necessary to teach folks in the country why Native Americans do not see Thanksgiving as a reason for celebration and why it is instead for them a reason for mourning. That is predicated on the willingness of Americans to study history instead of accepting as history a bunch of sanitized founding-myths that are designed to confirm nationalism and end up perpetuating racist attitudes.

I think it is also important to involve Native Americans systematically in our attempt to right the wrong. Historically, Euro-Americans have tended to implement reforms in a very paternalistic way without even bothering to ask Native Americans their opinion. Since the founding of this country, federal policies toward First Nations have been designed for the benefit of Euro-Americans. Contrary to the appearances and the slogans, the General Allotment Act of 1887, for instance, was not initiated to improve the lives of Native Americans by doing away with the reservation system. It was implemented in part to seize control of more Indigenous land in the U.S. under the guise of humanitarian reforms.

The tendency to appoint Native Americans like Deb Haaland in the highest echelons of the government is a move in the right direction. The high-handed and paternalistic behavior of the U.S. government has made Native Americans wary of the federal bureaucracy. Placing Native Americans in positions of power could help change perceptions. Such initiatives are also critical to launch sincere reforms that are actually meant to serve First Nations.