Graduate Student Discovers Largest Slave Auction

Thanks to funding by a native Charlestonian whose ancestors traded enslaved people, Lauren Davila ’21 (M.A. ’23) uncovered the largest known domestic slave auction, which took place in Charleston, as a graduate student at the College.

As a graduate assistant with the College’s Center for the Study of Slavery in Charleston, Lauren Davila ’21 (M.A. ’23) spent mornings at her desk in her Charleston bedroom drinking coffee and scrolling through the Charleston County Library’s digitized copies of local newspapers published between 1808 and 1845. Assigned to identify slave auction ads, Davila reviewed hundreds of search results from every Charleston newspaper printed at the time. To avoid any repeated ads, she logged the number of enslaved people for sale in each, typically between 10 and 50. It was a monotonous task.

On a Tuesday morning in March 2022, however, Davila came across an ad that caused her to do a double take.

Davila couldn’t believe the words, partially obscured by handwritten marks, in front of her: “SIX HUNDRED.”

“At first, I thought it was a mistake, but knowing Charleston’s role in the domestic slave trade, I knew it had to be true,” says Davila. “I grabbed a book chronicling the largest known slave auction in the U.S. – it was 436.

“I immediately reached out to Dr. Powers about my find,” she continues, referring to her mentor, Bernard Powers, the director of the Center for the Study for Slavery in Charleston and professor emeritus of history.

“To say that I was surprised is to understate Lauren’s discovery,” says Powers. “I was shocked at the finding because of the number of people being sold, i.e., 600. I also thought about the site of the sale, which has a historical marker, but I immediately knew that no sign could convey the enormity of the despair and agony which must have been displayed as families and friends were separated forever on that fateful day in 1835.”

Now, thanks to Davila and a passionate team of researchers, the enormity of Charleston’s involvement in the domestic slave trade is coming to the forefront with new research, a new online walking tour and a new class at the College.

Slavery in the Family

The road to the discovery started with another discovery. At age 65 in 2018, Margaret Seidler learned that her ancestors included slave traders. In fact, her ancestors had been involved in the slavery business for nearly 100 years.

Her discovery lit a fire in the native Charlestonian who thought of all the other people who are unaware of how they might be connected to this dreadful time in U.S. history. Seidler spent hundreds of hours combing through Charleston’s newspapers from 1790 to 1834 and found more than 1,100 ads for the sale of more than 9,200 enslaved people by the business owned by her ancestor William Payne, whose office was at 32-34 Broad St.

Seidler wanted to establish a historic marker at the site and contacted Powers for scholarly support. Thanks to their efforts, the marker now sits prominently at 34 Broad St.

Seidler and Powers continued their collaboration to uncover the history of Charleston’s domestic slave trade. With funding from Seidler and her husband, Bob, the Center for the Study of Slavery was able to hire a graduate assistant to support their research.

The opportunity to dig deeper into the history of the U.S. domestic slave trade excited Davila, who was pursuing a Master of Arts in history with a public history concentration.

“I had read Dr. Powers’ book, Black Charlestonians, as an undergrad,” she says. “I never thought I’d have the chance to meet with him, let alone work with him.”

Register of Deeds

Seidler provided Davila with a list of known slave traders she had found during her research, and Davila began the arduous task of counting the number of enslaved people advertised in newspapers.

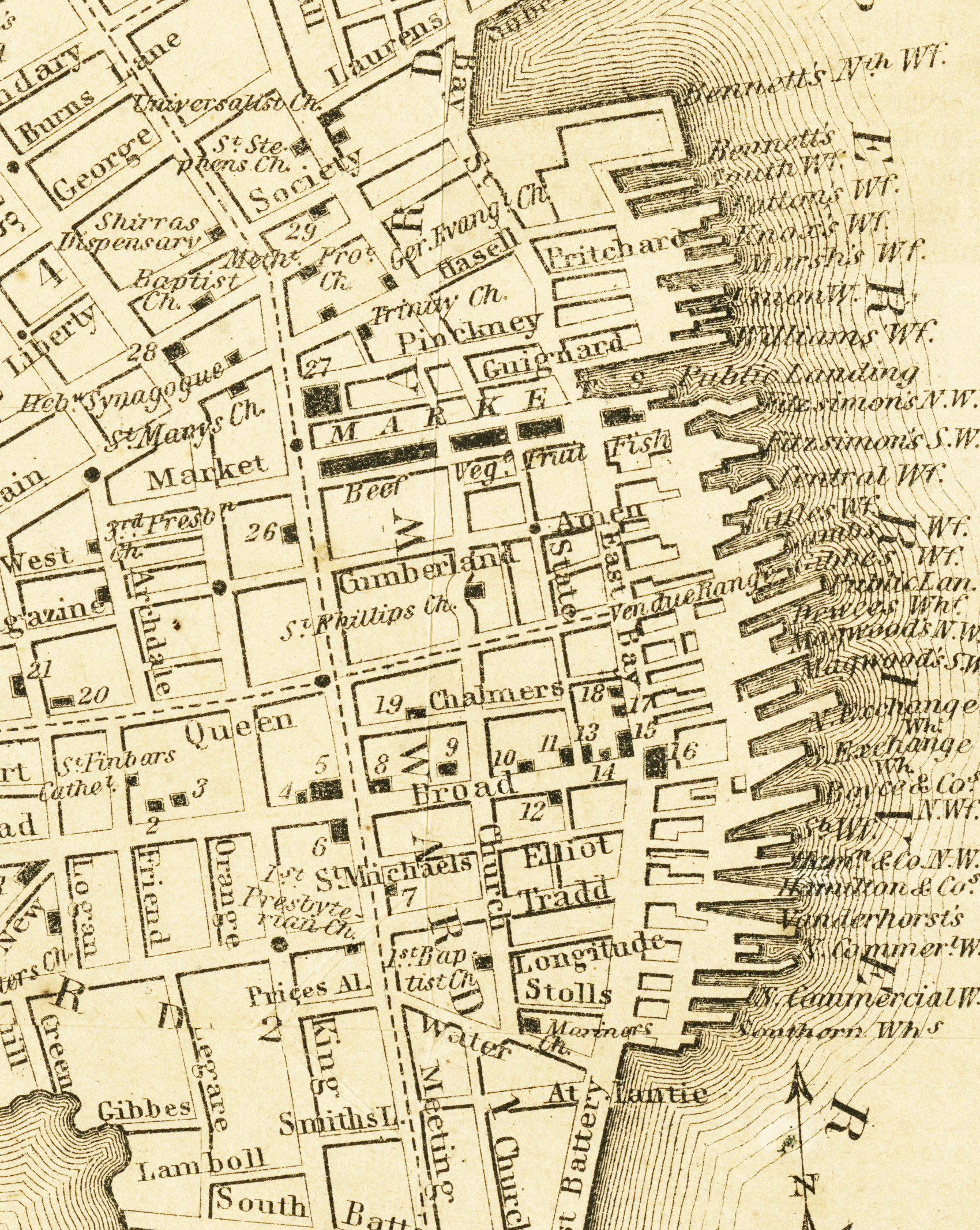

“There were more than 10 auctions in the newspapers every day that included the sale of 10 to 50 enslaved people,” says Davila. “Most of the auctions took place on the north side of the Exchange Building located on the corner of East Bay and Broad Street in downtown Charleston.”

One morning as she scrolled through the digitized copy of the Feb. 24, 1835, issue of the Charleston Courier, Davila discovered an ad in the fifth column on Page 3 by Jervey, Waring & White that gave her pause.

“THIS DAY, the 24th instant, and the day following, at the North side of the Custom-House, at 11 o’clock, will be sold, A very valuable GANG OF NEGROES. Accustomed to the culture of rice; consisting of SIX HUNDRED. Among them are Drivers, Carpenters, Coopers, and Boatmen.”

Shocked, Davila grabbed her copy of Anne Caroline Bailey’s The Weeping Time: Memory and the Largest Slave Auction in American History, which chronicles the largest known slave auction in the U.S. She checked the number: 436. She looked back at the words on her screen: SIX HUNDRED.

In addition to Powers, Davila also contacted Seidler. “I was sick to my stomach,” she says. “I imagined 600 people crowded together at that small intersection of Broad and East Bay being sold on the auction block. That didn’t count the prospective buyers and gawkers.”

Connecting the Dots

There were so many avenues to take with this discovery – trace where the slaves originated and where they were sold, profile the slave traders or profile the original slaveowners. Powers and Davila agreed that, for her master’s thesis, she should focus on the slave traders – specifically, the firm Jervey, Waring & White, owned by James Jervey, Class of 1842, Morton A. Waring and Alonzo J. White, who served on the College’s Board of Trustees.

Realizing the scope of the project, Seidler reached out to ProPublica reporter Jennifer Berry Hawes, whom she knew socially and who had previously joined her in researching her family’s involvement in the slave trade.

Hawes quickly found the name of the original owner of the 600 enslaved people who went up for auction: John Ball Jr. Through her research and research by Seidler about Ann Simons, John Ball Jr.’s wife, Hawes was able to provide context to the auction and a detailed account of the rice dynasty from its years as slaveholders (1698–1865) to present day. Ball had died at age 51 of malaria the year before, and now five of his plantations – and the enslaved people who worked them – were up for sale.

In addition to funding from the CSSC, thanks to the Seidlers, Davila received the Karen Chambers Fellowship from the College’s Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture to continue her research. As part of the fellowship, she shared her findings at an Avery Research Center luncheon in the spring of 2023 and wrote a synopsis of her thesis.

“With the funding, I was able to conduct research at the Register of Deeds in Charleston and create the website for a walking tour,” says Davila. “Dr. Powers gave me a lot of freedom. He always explained the significance of my findings and helped me determine my path.”

The research at the Register of Deeds proved fruitful. Davila determined the addresses of the slave-trading firms and pinpointed where they would be today. For example, she found that Jervey, Blake & Waring (renamed Jervey, Waring & White after Blake died in 1833) opened its offices in 1828 at 20 Broad St., which today is 24 Broad St.

Shining a Light

As she delved into the lives of the slave traders, Davila learned that while the auctions enriched their bank accounts and social standing, their involvement in human-trafficking was seldom mentioned. If their business was mentioned, it was as an auctioneer or broker.

“These slave traders were prominent men in Charleston society,” explains Davila. “In addition to their slave-trading firms, they held positions in banks, the courts and city government. They also served as active leaders in the city’s benevolent societies. In some cases, they were even chairmen of their church vestry.”

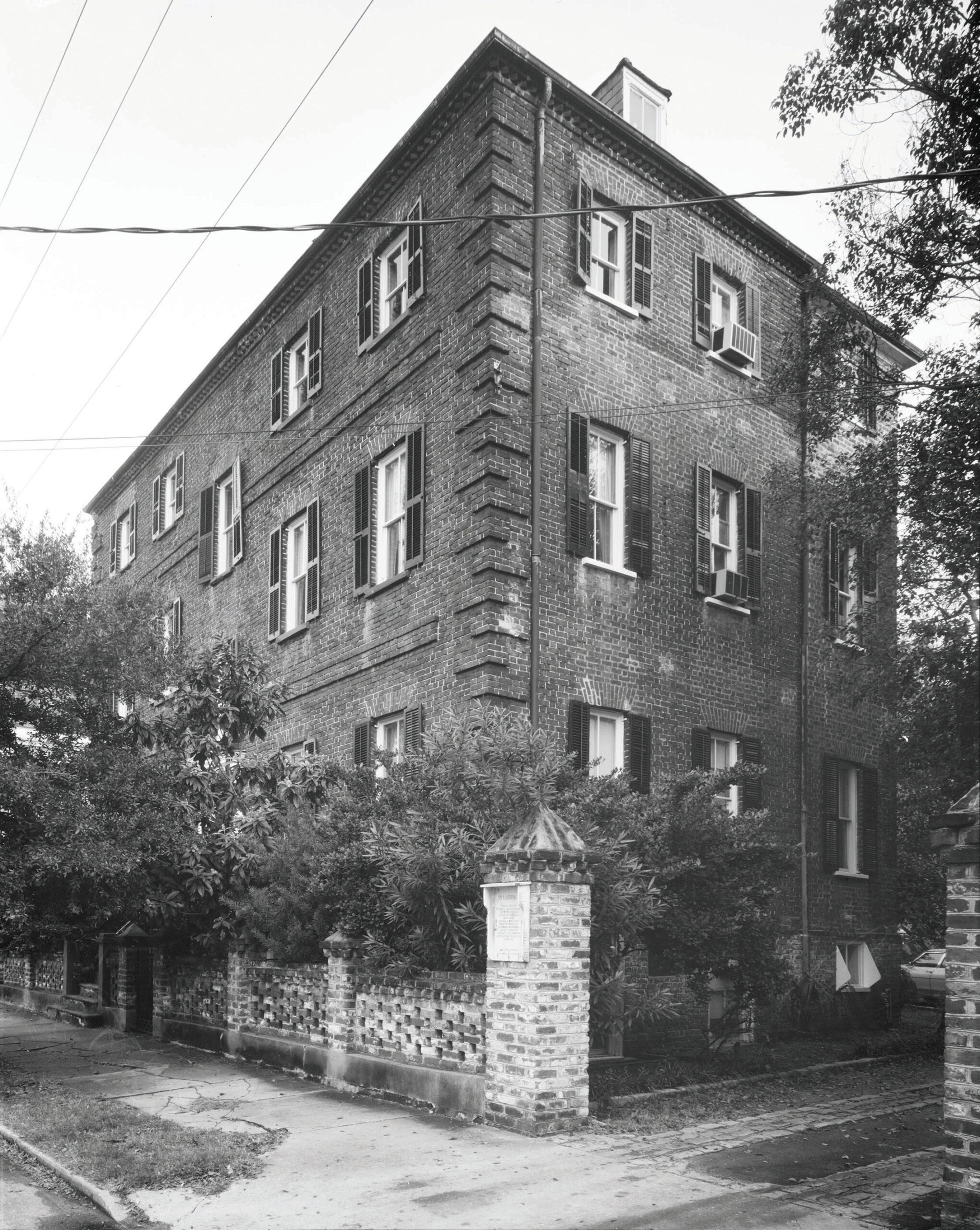

Growing up on Pawleys Island, S.C., Davila had felt that African American history wasn’t really shared – and, here again, she could see that the history of the domestic slave trade was largely obscured. The location of the firms was not marked, and the slave traders themselves had no mention of their role in their profiles. Instead, the members of one of Charleston’s biggest slave-trading firms are remembered as benefactors who contributed to society. Two homes in downtown Charleston, the James Jervey House and the Morton Waring House, bear their names to this day. While a person of distinction in society, Alonzo J. White is most remembered as connected to the slave trade because of his accounting books. He served as chairman of the Work House commissioners and reported the fees collected from the short-term incarceration and torture of enslaved people. He also recorded selling slaves out of his East Bay Street “kitchen,” a separate building on his property.

To get the story out to a broader audience, Davila laid out an online walking tour of the slave trade in Charleston’s business district. The history of the site and profiles of the slave traders are shared at each of the nine locations.

“I wanted to see what the domestic slave trade district looked like; it had never been defined,” says Seidler. “Thanks to Lauren’s work, we have taken a giant step forward.”

Adds Powers: “Lauren’s research has deepened our understanding of the domestic slave trade in our city and is foundational to the center’s efforts to identify, demarcate and further analyze the areas where this execrable human commerce occurred.”

For the 2023-24 academic year, Davila is teaching history at the College, including a course on slavery and the slave trade. She hopes to inspire more students to take up similar research through her new class. She also has plans to get her doctorate so she can delve deeper into what is now the largest domestic slave auction on record.

“What I found could easily have been missed,” says Davila, who, incidentally, received an A on her master’s thesis. “What’s really needed is more graduate assistants to scour the pages to find the many slave auctions that have not been documented. The center needs the research funding to lay the groundwork for the full picture of the domestic slave trade in Charleston.”