Biology Professor's Vein of Research

With the blood of horseshoe crabs critical to vaccines, biology professor Jody Beers hopes to improve survival rates.

If you’ve ever watched horseshoe crabs congregate at the high tide line to mate in the spring, you’ve witnessed something that has been going on for hundreds of millions of years.

But something else is at play now, too – a biomedical controversy. The horseshoe crabs’ blue blood is prized by the medical industry to use in tests for pathogens in vaccines and intravenous drugs. Their value, however, is threatening not only their existence, but that of the red knot shorebird since red knots depend on horseshoe crab eggs for food during their long migration.

Upwards of 30% of the crabs die in the bleeding process or after they’re released, and no one knows how well the ones that survive do in reproducing afterward (a healthy female can lay up to 100,000 eggs per spawning season). Pharmaceutical companies are also interested in getting the best blood possible while improving post-harvesting survival rates.

Those are some of the areas of interest that Jody Beers, assistant professor of biology at the College, addresses in her research at the Hollings Marine Research Laboratory on James Island, S.C.

“I’m fascinated by horseshoe crabs because of their importance to so many different sectors,” says Beers, who hopes to uncover parameters that are critical in reducing mortality rates. “One of the reasons that environmental groups are concerned, and rightfully so, is the significance of removing up to 30% of the population, which is not trivial.”

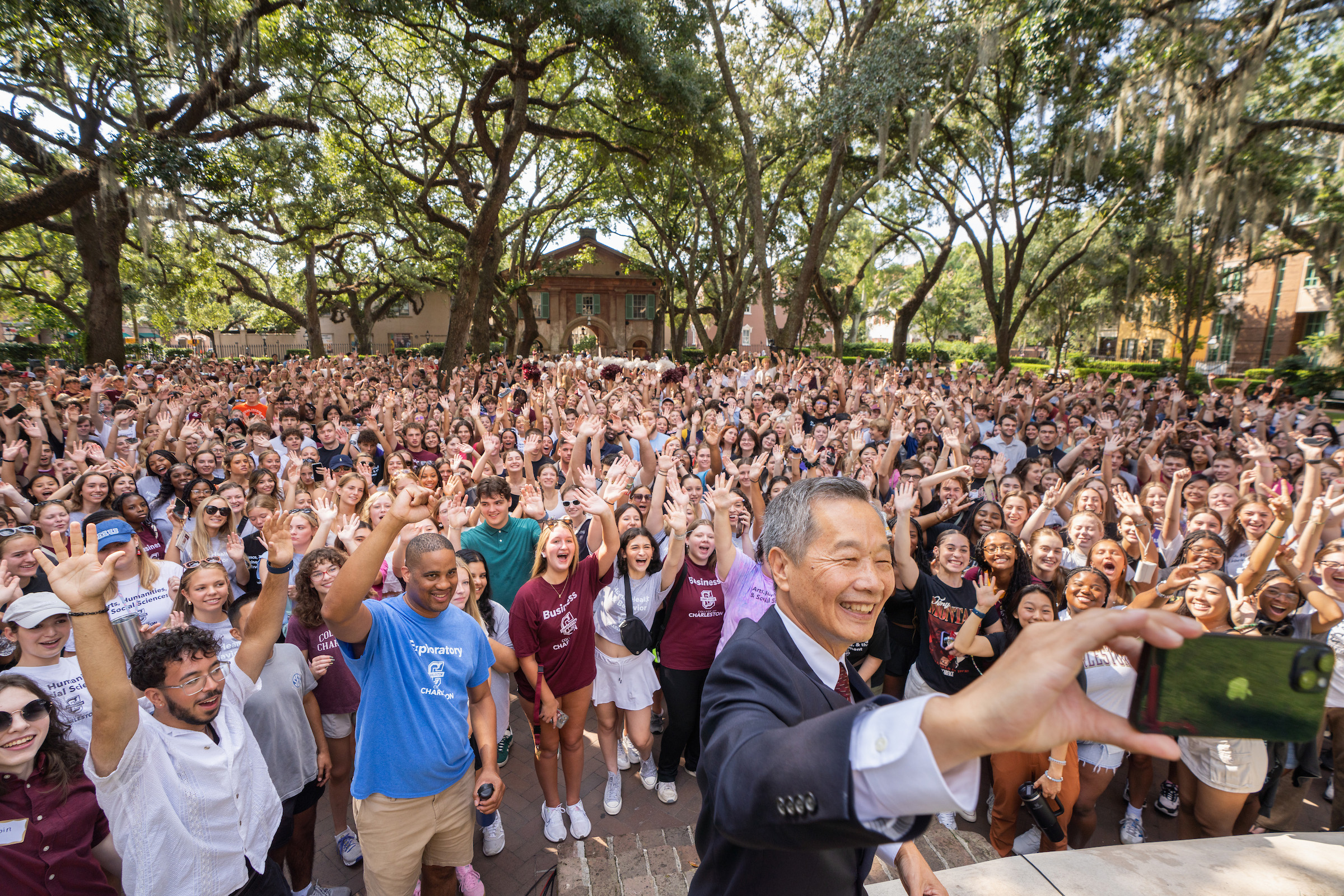

Holding ponds can get as hot as 85 degrees in summer, so Beers and her students conduct experiments on how temperature affects metabolic rates. Beers will also bleed the horseshoe crabs (above) to see how that affects their overall blood chemistry and physiology.

“We use an integrative approach, studying the whole animal down to the cellular and molecular level,” she says.

Science has been in Beers’ blood since Mrs. Jones’ biology class at Pleasant Valley Middle School in Effort, Pa. Raised on a horse farm, Beers fell in love with the ocean on a visit to a great aunt in Belmar, N.J., the same year.

“That was it,” she says. “I knew what I wanted to do from the seventh grade.”

Beers is a first-generation academic in her family, although it took her 12 years to complete her undergraduate degree at East Stroudsburg University. She took time off from her studies to raise two children and help run a construction business with her husband.

I tell my undergrad students that everyone has a different path,” she says. “I was persistent. I never wanted to do anything but the science.”

In 2010, after earning a master’s and then a doctorate at the University of Maine, she did her postdoctoral work at Stanford University. In 2019, Beers joined the faculty at the College, where she teaches Physiology and Cell Biology of Marine Organisms and General and Comparative Physiology, in addition to mentoring graduate students like Kerryanne Litzenberg.

“I’ve learned so much from working with her,” says Litzenberg, who is getting a master’s in marine biology. “I’ve gotten so much experience and learned so many different techniques that I don’t know I would have gotten anywhere else.”